- Region

- Águilas

- Alhama de Murcia

- Jumilla

- Lorca

- Los Alcázares

- Mazarrón

- San Javier

-

ALL AREAS & TOWNS

- AREAS

- SOUTH WEST

- MAR MENOR

- MURCIA CITY & CENTRAL

- NORTH & NORTH WEST

- TOWNS

- Abanilla

- Abarán

- Aguilas

- Alamillo

- Alcantarilla

- Aledo

- Alhama de Murcia

- Archena

- Balsicas

- Blanca

- Bolnuevo

- Bullas

- Cañadas del Romero

- Cabo de Palos

- Calasparra

- Camping Bolnuevo

- Campo De Ricote

- Camposol

- Canada De La Lena

- Caravaca de la Cruz

- Cartagena

- Cehegin

- Ceuti

- Cieza

- Condado de Alhama

- Corvera

- Costa Cálida

- Cuevas De Almanzora

- Cuevas de Reyllo

- El Carmoli

- El Mojon

- El Molino (Puerto Lumbreras)

- El Pareton / Cantareros

- El Raso

- El Valle Golf Resort

- Fortuna

- Fuente Alamo

- Hacienda del Alamo Golf Resort

- Hacienda Riquelme Golf Resort

- Isla Plana

- Islas Menores & Mar de Cristal

- Jumilla

- La Azohia

- La Charca

- La Manga Club

- La Manga del Mar Menor

- La Pinilla

- La Puebla

- La Torre

- La Torre Golf Resort

- La Unión

- Las Palas

- Las Ramblas

- Las Ramblas Golf

- Las Torres de Cotillas

- Leiva

- Librilla

- Lo Pagan

- Lo Santiago

- Lorca

- Lorquí

- Los Alcázares

- Los Balcones

- Los Belones

- Los Canovas

- Los Nietos

- Los Perez (Tallante)

- Los Urrutias

- Los Ventorrillos

- Mar De Cristal

- Mar Menor

- Mar Menor Golf Resort

- Mazarrón

- Mazarrón Country Club

- Molina de Segura

- Moratalla

- Mula

- Murcia City

- Murcia Property

- Pareton

- Peraleja Golf Resort

- Perin

- Pilar de la Horadada

- Pinar de Campoverde

- Pinoso

- Playa Honda

- Playa Honda / Playa Paraíso

- Pliego

- Portmán

- Pozo Estrecho

- Puerto de Mazarrón

- Puerto Lumbreras

- Puntas De Calnegre

- Region of Murcia

- Ricote

- Roda Golf Resort

- Roldan

- Roldan and Lo Ferro

- San Javier

- San Pedro del Pinatar

- Santiago de la Ribera

- Sierra Espuña

- Sucina

- Tallante

- Terrazas de la Torre Golf Resort

- Torre Pacheco

- Totana

- What's On Weekly Bulletin

- Yecla

- EDITIONS:

Spanish News Today

Spanish News Today

Alicante Today

Alicante Today

Andalucia Today

Andalucia Today

History of Pilar de la Horadada

Romans, Moors, modern tourism and the Christian Reconquist have all left their mark on Pilar de la Horadada

This area of Spain has attracted settlers since prehistory, and although there are no prehistoric sites in Pilar de la Horadada, there are traces of mankind in the Valencia region dating back to the lower Paleolithic, and 250,000BC.

This area of Spain has attracted settlers since prehistory, and although there are no prehistoric sites in Pilar de la Horadada, there are traces of mankind in the Valencia region dating back to the lower Paleolithic, and 250,000BC.

The first culture to leave substantial traces in thia area is the Iberian culture. Iberian traders lived and worked here during the Iron Age, the term "Iberians" encompassing the range of peoples who lived along the Mediterranean fringes between Upper Andalucía and the River Hérault, in the South of France, from the 8th to the 1st century BC. This covered an area including modern day Andalucía, Albacete, Murcia, Valencia, Catalunya and some parts of Aragón.

During this 600 year period artifacts recovered during excavations show how the knowledge and technology of the Iberian peoples visibly changed as they absorbed technology and influences through their commercial and colonial contacts with other cultures trading along the Mediterranean coastline; the Phoenicians, the Greeks and, later on, the Carthaginians and Romans. In the end they disappeared as a definable culture of their own, absorbing the influences of Rome to gradually became indefinably “romanised”, to the extent that by 150BC, they had ceased to exist as “Iberians”.( To see more about the Iberians, see an extensive report relating to their presence in the Murcia region,which would have been equally relevant to the people moving through this area before Murcia was even divided from Pilar by a modern boundary).

During this 600 year period artifacts recovered during excavations show how the knowledge and technology of the Iberian peoples visibly changed as they absorbed technology and influences through their commercial and colonial contacts with other cultures trading along the Mediterranean coastline; the Phoenicians, the Greeks and, later on, the Carthaginians and Romans. In the end they disappeared as a definable culture of their own, absorbing the influences of Rome to gradually became indefinably “romanised”, to the extent that by 150BC, they had ceased to exist as “Iberians”.( To see more about the Iberians, see an extensive report relating to their presence in the Murcia region,which would have been equally relevant to the people moving through this area before Murcia was even divided from Pilar by a modern boundary).

Ceramics and coins show that Greek traders travelled through the area using the “Via Heraclea”, which the Carthaginians later referred to as the Road of Hannibal, and a collection of coins on display in the municipal archaeological museum today is testament to their presence.

In 226 BC the Ebro treaty placed what is now Pilar de la Horadada under the control of the Carthaginians, who founded the city of Quart Hadast in the location that later became Cartagena, but the treaty was broken in 219BC when Hannibal took his army from Quart Hadast ( Cartagena) and crossed the River Ebro to take Sagunto, sparking off the Second Punic Wars and prompting a Roman Invasion in 202BC. The Romans rebuilt Quart Hadast, renamed it Carthago Nova and constructed the Via Augusta, an important trading road which ran 1500km from Cádiz through to the Pyrenees, linking into the network of roads leading to Rome.

In 226 BC the Ebro treaty placed what is now Pilar de la Horadada under the control of the Carthaginians, who founded the city of Quart Hadast in the location that later became Cartagena, but the treaty was broken in 219BC when Hannibal took his army from Quart Hadast ( Cartagena) and crossed the River Ebro to take Sagunto, sparking off the Second Punic Wars and prompting a Roman Invasion in 202BC. The Romans rebuilt Quart Hadast, renamed it Carthago Nova and constructed the Via Augusta, an important trading road which ran 1500km from Cádiz through to the Pyrenees, linking into the network of roads leading to Rome.

Remains of agricultural “villae”, have been found which show signs of Roman construction dating back to this period, the settlement the Romans called Thiar ( now Pilar) most likely a stopping off point on the Via Augusta between Illici (Elche) and Carthago Nova (Cartagena).

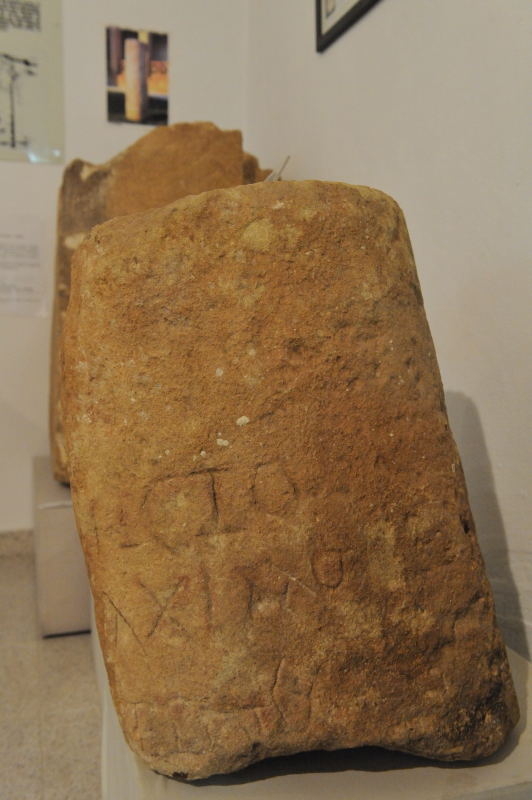

There are also remains of a Roman quarry in Pilar de la Horadada, on the coast near to La Torre de la  Horadada, which probably supplied stone used to pave this main Roman highway, a solid, well constructed road which was sometimes up to 1.8 metres in depth, as well as providing stone for private construction projects. The municipal archaeological museum has a life sized model showing the construction of the Via Augusta, and also one of the milestones found in the municipality which would have stood alongside it.

Horadada, which probably supplied stone used to pave this main Roman highway, a solid, well constructed road which was sometimes up to 1.8 metres in depth, as well as providing stone for private construction projects. The municipal archaeological museum has a life sized model showing the construction of the Via Augusta, and also one of the milestones found in the municipality which would have stood alongside it.

Shipwrecks found along the shore of Pilar de la Horadada suggest that there was also some commercial maritime traffic in the area, which was thus linked to Rome not only by road but also by sea.

As well as the road itself there is also evidence of the existence of Roman water deposits and other structures which would have provided rest to travellers along the Via Augusta: water was needed not only by troops, tradesmen and shepherds, but also by the cattle which were herded along the route, and the network of water channels and deposits was later conserved and used by the Moors. Indeed, many elements of the system were still used right through the Middle Ages and some even survive into the Modern era, including the drinking wells known as “La Conqueta”, “La Verea”, “Lo Montanero” and “Lo Romero”: although built between the 18th and 20th centuries they bear witness to far more ancient designs for making the most of the water available in an often dry and hostile landscape.

These infrastructures made it possible to supply water to both shepherds and their flocks, and as a result they frequently used the surrounding pasture land and transhumance routes.

These infrastructures made it possible to supply water to both shepherds and their flocks, and as a result they frequently used the surrounding pasture land and transhumance routes.

Following the end of the Roman occupation, the area underwent a turbulent period of occupation, as the Roman Empire split into two, paving the way for a series of Barbarian raids across Europe. First came the vandals, then the Visigoths, and although the Byzantians who represented one half of the Roman empire briefly regained the lands once held by the Romans, this was only for a short period and this area once again came under the control of the Visigoths. By 576 the nearby town of Orihuela was capital of the Visigoth province of Aurariola and by the time of the next important date of 713, Count Teodomiro ( or Tudmir) who was a nobleman employed in the royal guard of King Egica, had been given various plots of land on which he settled in the area of Elche.

In 713 the Moors invaded Spain, and as they swept through Visigoth territory, canny rulers realised that the most effective means of holding on to power was to make a deal with the better equipped invaders, and Tudmir reserved his place in history by signing the Pact of Tudmir, effectively recognizing the rule of the Muslim conquerors, whilst retaining his own right to rule the area he occupied.

In 713 the Moors invaded Spain, and as they swept through Visigoth territory, canny rulers realised that the most effective means of holding on to power was to make a deal with the better equipped invaders, and Tudmir reserved his place in history by signing the Pact of Tudmir, effectively recognizing the rule of the Muslim conquerors, whilst retaining his own right to rule the area he occupied.

The Moors continued to use the old road as an important trading route long the Mediterranean coast, and under their rule, which lasted until the beginning of the Christian Reconquist in the middle of the 13th century, Pilar de la Horadada was a predominantly agricultural community. The legacy from the following centuries consists not only of archaeological findings but also of many of the place names in the area.

The name of the Pilar de la Horadada, though, derives from one of the watchtowers built following the  departure of the Moors in 1492, when the last remaining Moorish Kingdom of Granada fell to Christian control (the Reconquista). Moors who refused to convert to Christianity were expelled, making thousands homeless. Some of these became pirates, attacking the coastline, stealing crops, taking hostages and driving settlers from their homes. A series of watchtowers were built along the coast to warn of attack, the tower in modern day Pilar named “Torre Horadada” on account of the holes in the ceilings of the different floors of the tower, which allowed sentinels to communicate more freely with one another. The same tower was to be used for many centuries in order to warn the inhabitants of incursions by raiders approaching from the sea.

departure of the Moors in 1492, when the last remaining Moorish Kingdom of Granada fell to Christian control (the Reconquista). Moors who refused to convert to Christianity were expelled, making thousands homeless. Some of these became pirates, attacking the coastline, stealing crops, taking hostages and driving settlers from their homes. A series of watchtowers were built along the coast to warn of attack, the tower in modern day Pilar named “Torre Horadada” on account of the holes in the ceilings of the different floors of the tower, which allowed sentinels to communicate more freely with one another. The same tower was to be used for many centuries in order to warn the inhabitants of incursions by raiders approaching from the sea.

Following the Christian Reconquista, Pilar de la Horadada became a frontier settlement between the kingdoms of Castile and Aragón, and it was at this point, in the early 16th century, that one of the most interesting phases in its history began.

The Reconquista took more than 200 years to complete, beginning with a push downwards by the great powers of Castile y León and Aragón. In the 13th century Spain was a series of independent kingdoms, which only became united when Isabella and Ferdinand married and ejected the Moors from Granada in 1492.

In the 13th century both of these two major powers were moving down into southern Spain, extending their own territories as they retook land from the Moors, and border disputes were common among the resurgent Spanish kingdoms: there was frequent conflict during the reigns of Fernando III of Castile and Jaime I of Aragón, and peace was not reached until the Treaty of Almizra was signed by Jaime I and his son-in-law, the future Alfonso X, in 1244. By this treaty the limits of the Kingdom of Valencia and the Kingdom of Murcia were established, and the border still marks the boundary of Pilar de la Horadada with the neighbouring municipality of San Pedro del Pinatar in the Autonomous Community of the Region of Murcia today. Disputes over the exact location of the boundary are still commonplace even in the 21st century, and the National Geographical institute has been called in to arbitrate in a modern day dispute which still continues today.

In the 13th century both of these two major powers were moving down into southern Spain, extending their own territories as they retook land from the Moors, and border disputes were common among the resurgent Spanish kingdoms: there was frequent conflict during the reigns of Fernando III of Castile and Jaime I of Aragón, and peace was not reached until the Treaty of Almizra was signed by Jaime I and his son-in-law, the future Alfonso X, in 1244. By this treaty the limits of the Kingdom of Valencia and the Kingdom of Murcia were established, and the border still marks the boundary of Pilar de la Horadada with the neighbouring municipality of San Pedro del Pinatar in the Autonomous Community of the Region of Murcia today. Disputes over the exact location of the boundary are still commonplace even in the 21st century, and the National Geographical institute has been called in to arbitrate in a modern day dispute which still continues today.

When Carlos II died without an heir in 1700 the War of the Spanish Succession broke out, lasting until 1714. Almost the whole of Catalunya and Valencia supported the House of Austria against Felipe of Anjou, and in 1707, just a few months after the Battle of Almansa, the regional laws of Valencia and Aragón were subjugated to those of Castile.

At this time there was already a significant population in the countryside around Horadada: in 1750 the population was around 300, most of them living in country dwellings dotted around a small place of worship known as the Capilla del Sagrado Corazón (Chapel of the Sacred Heart). This church had been built in 1616, but in 1752 Bishop Gómez de Terán decided to build the parish church of Nuestra Señora del Pilar y Sagrado Corazón in its place, and by 1758 the church owned the land in front of it and behind it. This is the area which is now the central town square in which the building stands.

At this time there was already a significant population in the countryside around Horadada: in 1750 the population was around 300, most of them living in country dwellings dotted around a small place of worship known as the Capilla del Sagrado Corazón (Chapel of the Sacred Heart). This church had been built in 1616, but in 1752 Bishop Gómez de Terán decided to build the parish church of Nuestra Señora del Pilar y Sagrado Corazón in its place, and by 1758 the church owned the land in front of it and behind it. This is the area which is now the central town square in which the building stands.

The naming of the church led for the first time to the settlement being known as Pilar de la Horadada, and with their new status and increasing prosperity the inhabitants began to finally abandon the remnants of the old Via Augusta, building new roads and working the soil until the old Roman road was lost without trace.

It should not be forgotten that until not long before this time there had still been frequent Berber pirate raids on the region’s coastline, and these had serious effects on inland areas. An agreement had been reached to end the raids and all that was left to stir the inhabitants’ unhappy memories was the network of watchtowers which were used to warn citizens of approaching danger by means of beacons which were lit on the top of each tower. Over time many of the towers were dismantled, while others were acquired by new owners and adapted to different uses. This was the case of the Horadada watchtower, originally built during the reign of Felipe II in 1591, which by 1905 had become a residential palace for the Counts of Roche. Nowadays the tower has been awarded the status of Item of Cultural Interest.

The early 19th century was, in general, a time of economic prosperity for the countryside of Horadada. The spark which set off this period of economic growth was the Decree of 11th October 1835, known as the Mendiazábal Law, which ruled that all land and buildings belonging to the Church passed into the hands of the State. Among these properties was the Dehesa de San Ginés, also known as Matamoros en Campoamor. This country estate had been in the hands of the Church since 1350, when the church and the religious brotherhood were created, and a previous attempt to wrest it from their control had failed in 1822. In the meantime the State intervened and sold a two-thirds share in the property to William Gorman Maclure, future father-in-law of the poet Ramón de Campoamor, a share which was returned to the Order of the Blessed Virgin Mary of Mercy after two years. In 1835, though, the estate again fell into the hands of Maclure.

The early 19th century was, in general, a time of economic prosperity for the countryside of Horadada. The spark which set off this period of economic growth was the Decree of 11th October 1835, known as the Mendiazábal Law, which ruled that all land and buildings belonging to the Church passed into the hands of the State. Among these properties was the Dehesa de San Ginés, also known as Matamoros en Campoamor. This country estate had been in the hands of the Church since 1350, when the church and the religious brotherhood were created, and a previous attempt to wrest it from their control had failed in 1822. In the meantime the State intervened and sold a two-thirds share in the property to William Gorman Maclure, future father-in-law of the poet Ramón de Campoamor, a share which was returned to the Order of the Blessed Virgin Mary of Mercy after two years. In 1835, though, the estate again fell into the hands of Maclure.

The current church-tower was built in 1899 after the previous one was destroyed in a major earthquake which flattened much of Torrevieja, and in 1976 the current church replaced the 18th century construction on the same site, although maintaining the 19th century tower.

In 1929 the Sociedad Agrícola Instructiva was created in Pilar de la Horadada, an organization which remained operative until 1935. The following year saw the outbreak of the Civil War, and it was in this context that the CNT and UGT trades unions merged in August 1936. Pilar de la Horadada supported the Republican side in the War, and various different bulletins were published in the course of the conflict, the most famous being the first, entitled “Boletín informativo El Barracón”. This was founded in Lo Monte, and both civilians and military men took part in writing it.

In 1929 the Sociedad Agrícola Instructiva was created in Pilar de la Horadada, an organization which remained operative until 1935. The following year saw the outbreak of the Civil War, and it was in this context that the CNT and UGT trades unions merged in August 1936. Pilar de la Horadada supported the Republican side in the War, and various different bulletins were published in the course of the conflict, the most famous being the first, entitled “Boletín informativo El Barracón”. This was founded in Lo Monte, and both civilians and military men took part in writing it.

As in the rest of Spain, the scars of the Civil War took time to heal, and perhaps more so in Pilar de la Horadada, where the inhabitants felt isolated from the local politicians of Orihuela, 36 kilometres away, under whose jurisdiction they fell. Economically and socially they were neglected, and as a result the calls became ever louder for independence. The locals were aware of the potential in their town for growth in both agriculture and tourism, and were unhappy at paying the high taxes demanded by the Town Hall in Orihuela. In addition, the construction in the 1970s of the Tajo-Segura water supply canal, which runs around the town, supplied additional irrigation to local agriculture and strengthened the town’s economic growth, and this in turn led to it growing in size and population.

On 30th July 1986, after many years of negotiations, the popular movement of the town’s 6,000-plus citizens gained its reward and Pilar de la Horadada was awarded the status of Municipality, thus gaining its own Town Hall.

Since then the municipality has grown continually and sustainably. Only 20 years ago just 8,000 people lived here, but the ever wider range of services now cater for as many as 70 nationalities among the more than 23,000 inhabitants, all of whom enjoy the local holiday which is celebrated every 30th July in commemoration of the separation from Orihuela.

Since then the municipality has grown continually and sustainably. Only 20 years ago just 8,000 people lived here, but the ever wider range of services now cater for as many as 70 nationalities among the more than 23,000 inhabitants, all of whom enjoy the local holiday which is celebrated every 30th July in commemoration of the separation from Orihuela.

Today the municipality has a thriving services sector servicing the summer tourist trade which has grown out of the residential construction in the Torre de Horadada beachside area, also fuelled by the Campoverde urbanisation, home to around 5000 multinational inhabitants, just a few kilometres from the main town and beach and the golf course. Tourism also adds fuel to associated industries catering for the businesses who service the tourism sector.

Agriculture remains an important bastion of the local economy, and the municipality also has an industrial park.