- Region

- Águilas

- Alhama de Murcia

- Jumilla

- Lorca

- Los Alcázares

- Mazarrón

- San Javier

-

ALL AREAS & TOWNS

- AREAS

- SOUTH WEST

- MAR MENOR

- MURCIA CITY & CENTRAL

- NORTH & NORTH WEST

- TOWNS

- Abanilla

- Abarán

- Aguilas

- Alamillo

- Alcantarilla

- Aledo

- Alhama de Murcia

- Archena

- Balsicas

- Blanca

- Bolnuevo

- Bullas

- Cañadas del Romero

- Cabo de Palos

- Calasparra

- Camping Bolnuevo

- Campo De Ricote

- Camposol

- Canada De La Lena

- Caravaca de la Cruz

- Cartagena

- Cehegin

- Ceuti

- Cieza

- Condado de Alhama

- Corvera

- Costa Cálida

- Cuevas De Almanzora

- Cuevas de Reyllo

- El Carmoli

- El Mojon

- El Molino (Puerto Lumbreras)

- El Pareton / Cantareros

- El Raso

- El Valle Golf Resort

- Fortuna

- Fuente Alamo

- Hacienda del Alamo Golf Resort

- Hacienda Riquelme Golf Resort

- Isla Plana

- Islas Menores & Mar de Cristal

- Jumilla

- La Azohia

- La Charca

- La Manga Club

- La Manga del Mar Menor

- La Pinilla

- La Puebla

- La Torre

- La Torre Golf Resort

- La Unión

- Las Palas

- Las Ramblas

- Las Ramblas Golf

- Las Torres de Cotillas

- Leiva

- Librilla

- Lo Pagan

- Lo Santiago

- Lorca

- Lorquí

- Los Alcázares

- Los Balcones

- Los Belones

- Los Canovas

- Los Nietos

- Los Perez (Tallante)

- Los Urrutias

- Los Ventorrillos

- Mar De Cristal

- Mar Menor

- Mar Menor Golf Resort

- Mazarrón

- Mazarrón Country Club

- Molina de Segura

- Moratalla

- Mula

- Murcia City

- Murcia Property

- Pareton

- Peraleja Golf Resort

- Perin

- Pilar de la Horadada

- Pinar de Campoverde

- Pinoso

- Playa Honda

- Playa Honda / Playa Paraíso

- Pliego

- Portmán

- Pozo Estrecho

- Puerto de Mazarrón

- Puerto Lumbreras

- Puntas De Calnegre

- Region of Murcia

- Ricote

- Roda Golf Resort

- Roldan

- Roldan and Lo Ferro

- San Javier

- San Pedro del Pinatar

- Santiago de la Ribera

- Sierra Espuña

- Sucina

- Tallante

- Terrazas de la Torre Golf Resort

- Torre Pacheco

- Totana

- What's On Weekly Bulletin

- Yecla

- EDITIONS:

Spanish News Today

Spanish News Today

Alicante Today

Alicante Today

Andalucia Today

Andalucia Today

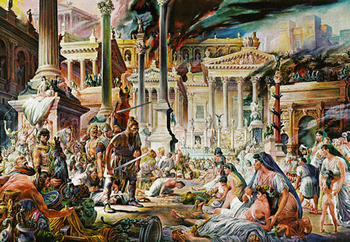

A history of Cartagena, part 3: from the 5th century to the 15th century

From the Visigoths and the Moors to the Reconquista and the Catholic Monarchs

By the fall of the Roman Empire in western Europe in 476 AD the city of Cartagena had lived through various periods of growth, wealth and splendor. The area had been home to pre-historic Man for many thousands of years – see the first part of the history of Cartagena- and then, over a period of around a thousand years starting in approximately 700 BC, the strategic advantages of its safe natural harbour and hilltop defences had led to it growing and developing.

This growth and consolidation took place first under the confederation of Tartessos, then with the colonization of the Iberians, the founding of Qart-Hadast by the Carthaginians, and lastly with centuries under the Roman Empire.

But the last years of Rome had been a period of decadence and decline, and Cartagena, along with the rest of the Empire, was now vulnerable to attack by other cultures…

The Visigoths and the Byzantines

From the little of which we can be certain the fifth century was, in Cartagena and the rest of the Iberian Peninsula, an unsettled time, as when the western Roman Empire fell it paved the way for a series of raids across Europe by the Barbarians and other tribes.

The Roman Empire was now divided into two: it was the western part which was invaded and crumbled in 476, although the eastern (or “Byzantine”) Empire survived for another thousand years or so, with its capital in Constantinople. However, almost as its last legacy to Spain, the Romans had introduced Christianity as the official religion by the late 4th century.

The Romans were actually ejected from Cartagena by the Vandals fifty years before the fall of the Empire in 409. In a subsequent battle which was won by the Visigoths in 425 the city was reportedly laid to waste, and then the Byzantines occupied the area in 551.

This occurred when the troops of the Emperor Justinian embarked on a campaign to recover the territories which had belonged to the western Roman Empire. In a deal which resolved a Visigoth power struggle they took Cartagena and made it the capital of the province of Spania, which included land from Málaga to Cartagena, calling the city Carthago Spartaria and re-building it.

This is a very confusing period of history in Spain – not for nothing is it referred to as the Dark Ages in northern Europe – but what remains clear is that the population of Cartagena was still fundamentally Christian at this point. San Leandro of Sevilla, who became archbishop of his adopted city, was born in Cartagena, and he and his family (including his brother San Hermenegildo) were actually quite happy under Visigoth rule before the Byzantines arrived: this led to their being persecuted and the family fled to Sevilla, later leaving documents showing very strong anti-Byzantine feelings.

The Byzantine domination of Cartagena is scarcely documented, but there is a  piece called the Comenciolo stone, which is still preserved in the Archaeological Museum. The inscription states that "Comenciolo was the Magister Militium Spanie", the highest authority sent to Hispania by the Emperor, and that he undertook a significant fortification of the city which lasted until 589, making good use of the existing walled structure which dated back to the 3rd and 4th centuries.

piece called the Comenciolo stone, which is still preserved in the Archaeological Museum. The inscription states that "Comenciolo was the Magister Militium Spanie", the highest authority sent to Hispania by the Emperor, and that he undertook a significant fortification of the city which lasted until 589, making good use of the existing walled structure which dated back to the 3rd and 4th centuries.

Relative peace endured until approximately 620, when the Visigoths returned and took Cartagena by force. There followed one of the darkest chapters in the city’s history, as a chieftain named Suintila dismantled all of the city’s fortifications, leaving it as little more than a fishing port.

Cartagena under the Moors

But in Cartagena and the rest of southern Spain, the chaos of the Dark Ages was to be brought to an abrupt end at the start of the 8th century, when tribal armies from Africa under the orders of Tarik began a campaign to conquer Visigoth Hispania. In 713, the troops of Abd al-Aziz undertook the conquest of the south-east and victory in what is now the Region of Murcia was achieved by means of a signed treaty (the Pact of Tudmir).

tribal armies from Africa under the orders of Tarik began a campaign to conquer Visigoth Hispania. In 713, the troops of Abd al-Aziz undertook the conquest of the south-east and victory in what is now the Region of Murcia was achieved by means of a signed treaty (the Pact of Tudmir).

This agreement effectively allowed the Visigoth leader Tudmir, or Theodomir, to remain in power as a puppet leader, but on his death around twenty years later his kingdom formed part of Al-Andalus under fully Moorish rule.

For Cartagena this meant the reconstruction and recovery of the city following the dark days under the Visigoths. The city was named “Qartayannat al-Halfa” by the Moors, and while this eventually developed or reverted to “Cartagena” other place names in the municipality such as La Azohía and Mandarache have survived ever since. From the 10th century onwards Cartagena is mentioned by various Moorish writers, always included within the Kingdom of Al-Andalus.

Still in the 8th century Abderramán I made the city a naval base, while under Abderramán III two hundred years later the lead and silver mines of Sierra Minera had made it one of the main ports of Al-Ándalus. In the middle of the 12th century, geographer al-Idrisi stated that Cartagena was "a city dating back to ancient, remote times, and the port gives refuge to ships both great and small", and the same author describes the land as "very fertile and full of natural resources ".

Life in Cartagena under the Moors

By the 11th and 12th centuries Cartagena was a fully developed Islamic city. The Moors were established in the medina on the slopes of the Monte de la  Concepción, a wall had been built around the city, and work had begun on the citadel at the top. On the northern side of the hill was the “arrabal”, the poorer quarter, and on the west was the district of Gomera, stretching down to the port.

Concepción, a wall had been built around the city, and work had begun on the citadel at the top. On the northern side of the hill was the “arrabal”, the poorer quarter, and on the west was the district of Gomera, stretching down to the port.

The mosque stood at the point where the three areas met, close to where the remains of the cathedral of Santa María la Vieja stand today. The maqbara (cementery) was outside the city wall, near where Calle Jara is today, and the city had three gates: one opposite the docks, and one on either side of the arrabal, and these opened out onto the roads to Murcia and San Ginés de la Jara.

Outside the city wall, meanwhile, the Moors brought with them the same agricultural revolution as in the rest of Spain, and recreational and farming areas developed. There was a market garden in what is now the district of San Antón, and away from the areas with irrigation ditches cereals were grown alongside almonds, olives and carobs in the arid farmland.

In the early 13th century Cartagena and the surrounding area had between 3,000 and 4,000 inhabitants, most of them converts to the Muslim religion, with the exception of some groups of defiant Christians who maintained their places of worship: this is the case in San Ginés de la Jara, where the ruins of small Christian chapels can be seen on the hillside near the Monastery.

The Reconquista and beyond

In what is now the Region of Murcia the “Reconquista” from the Moors was almost completed by the troops of Fernando III  in 1243, and the area was taken over by the Crown of Castilla by means of the document of "the Capitulations of Alcaraz."

in 1243, and the area was taken over by the Crown of Castilla by means of the document of "the Capitulations of Alcaraz."

However, the capitulation of Cartagena had to be enforced, as the city resisted the terms of Alcaraz and held out until two years later, when Castilian reinforcements arrived by ship from the north and stormed the fortified city.

At this point Murcia, especially the west of the region and the coast, effectively became frontier territory, lying on the edge of Christian Castilla in dangerous proximity to the Nazrid kingdom of Granada, and by the terms of the Alcaraz treaty the rights of those Muslims who remained were to be protected under the rule of Fernando and his son, Alfonso X.

In 1250 the Christian Diocese of Cartagena was re-established, and on succeeding his father in 1252 Alfonso X "El Sabio" (The Wise) gave the city more rights over the money from its own grain and wine production. This led to the arrival of Augustine monks from Cornellá to found the monastery of San Ginés de la Jara, and during the same period the first of Cartagena’s cathedrals was built.

This request was granted, and the situation has remained thus for over 700 years since, although the name of Cartagena is still retained under the terms of the permission given by Pope Innocent IV. In the eyes of those who campaign for a separate province of Cartagena this is still seen as an injustice, and calls for the Bishop’s seat to be returned to the port city are not infrequent.

Troubled times in the 13th, 14th and 15th centuries

The municipal boundaries awarded to Cartagena in 1254 included the land between the sea and a line from La Azohía to Fuente Álamo, then following the Rambla del Albujón east to the Mar Menor. Within this area, after the quashing of the Mudéjar uprising, there was a radical process of eliminating the Muslim population and replacing it with Christians, and any Muslim families who wished to remain in the region were forced to convert to Christianity.

But repopulating Cartagena with “good Christian stock” was no easy task: it was hard to tempt Christians to move down to the region from Castile, the efforts to recruit new settlers from Catalunya fell short of expectations, and the growing menace of Berber coastal raids and ongoing scurries along the border with Granada made the fringes of the Region a dangerous place to live.

Furthermore, a series of epidemics including the Black Death of 1348 further reduced the population, and the frailty of Cartagena’s agriculture in such a dry climate certainly didn’t make matters any better.

The final years of Alfonso X’s reign were marked by a dark period for all of  Castile due to confrontations between the monarchy and the nobility and the disputed rights of succession following the death of the King’s eldest son. At this point in time, Spain can be said to have been divided into five "kingdoms", with control of Cartagena fluctuating between Castile and Aragón in the struggles which followed.

Castile due to confrontations between the monarchy and the nobility and the disputed rights of succession following the death of the King’s eldest son. At this point in time, Spain can be said to have been divided into five "kingdoms", with control of Cartagena fluctuating between Castile and Aragón in the struggles which followed.

The Kingdom of Murcia was occupied by Jaime II of Aragón in 1296, but after the Sentence of Torrellas in 1304 Castilla recovered most of its land, leaving just part of modern-day Alicante and Cartagena to Aragón. A year later, thanks to the insistence of the military governor, Don Juan Manuel, Cartagena became a part of Castile again.

Under Pedro I (1350-1369), Cartagena saw action as a naval port in the struggle against the Crown of Aragón, bringing the city into severe danger and causing hardships to the inhabitants when it was besieged by Aragón in 1357.

In the reign of Enrique III (1390-1406), the most important feature of the kingdom of Murcia was the quarrel between Manueles and Fajardos, two families engaged in a long power struggle which lasted until peace arrived with the reign of the Catholic monarchs in the latter part of the 15th century.

These struggles affected Cartagena, especially from the 15th century onwards, after military governor Alonso Yáñez Fajardo died. He had been in control of the city and the castle of Cartagena, and his death caused a dispute between the two parties, with the Manueles twice attempting to take the castle by force after Pedro Fajardo took control of the city in 1465.

Peace under the Catholic Monarchs

With the accession to the throne of the Catholic Monarchs, Isabel I of Castile  and Fernando II of Aragón in 1474, the two major crowns were at last united, the political crisis abated and peace returned. Cartagena became an important operational base for the Mediterranean policy of Isabella and Fernando, and in 1495 the "Gran Capitán" Gonzalo Fernández de Córdoba embarked in the port on his way to Naples to fight in the First Italian War, while trading ships going to the north of Africa also sailed from Cartagena.

and Fernando II of Aragón in 1474, the two major crowns were at last united, the political crisis abated and peace returned. Cartagena became an important operational base for the Mediterranean policy of Isabella and Fernando, and in 1495 the "Gran Capitán" Gonzalo Fernández de Córdoba embarked in the port on his way to Naples to fight in the First Italian War, while trading ships going to the north of Africa also sailed from Cartagena.

In 1493 the Franciscans took over the monastery of San Ginés de la Jara, and ten years later, after sixty years of military governorships, the city returned to being a direct Crown dependency. In 1532 the city acquired Campo Nubla, a pasture land between Murcia and Lorca which is near the present-day town of Las Palas, and approached what promised to be a new era of stability with every prospect of continuing to develop as one of the most important cities in Spain.

The fourth in this series of articles traces the history and development of Cartagena from the early 16th century to the present day.